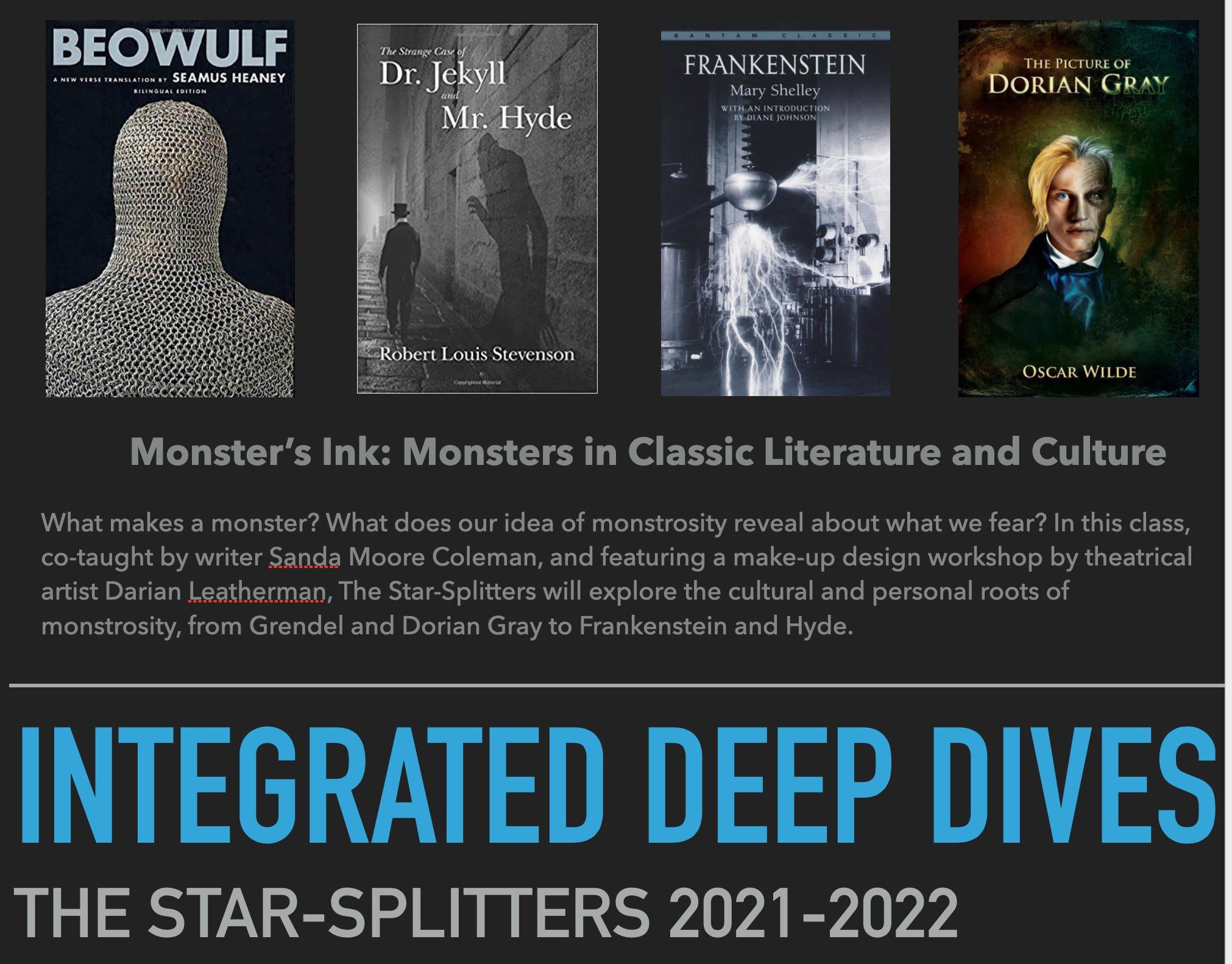

Monsters' Ink: Monsters in Literature and Culture

In this deep-dive, co-taught by Sanda Moore Coleman, we investigated classic monsters, modern monsters, and the question “What Makes a Monster?” from a number of angles of vision. We read significant excerpts from Beowulf and Frankenstein, read two Shirley Jackson stories, and read the whole of Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,--all with an eye toward seeing how such works are manifestations of fears--both personal and cultural--so that people might be better able to be in meaningful conversation with those fears, from the clash of worldviews that gave rise to Beowulf to the rapid cultural and technological changes that shaped the Romantic and Victorian Eras and thus shaped Mary Shelley's monster and Dr. Jekyll's division. In so doing, we recalled that, etymologically, "monster" is rooted in "thinking."

We looked, too, at how monsters in film have manifested cultural fears, from The Blob to Godzilla. Comedic films also can deal meaningfully with fears, we discovered, as with Chaplin's Modern Times, from 1938, which explored a fear of mechanization. (In our discussion of that movie, we were able to apply Henri Bergson's theories of comedy, which we learned about last year, and which were relatively new when Chaplin's film was made).

We also learned about the difference between explicit and implicit evidence (a concept we then applied in our Constitutional law class when learning about expressed vs. implied powers of the Constitution), and about how tone in writing is created through diction and imagery.

Students demonstrated their understanding in a number of ways. They wrote an essay analyzing Dr. Frankenstein's tone in a famous passage from Mary Shelley's novel. They exercised their understanding of explicit and implicit textual evidence by crafting their own versions of the monster Grendel from Beowulf, accompanied by essays that analyzed the text to show how the work of their hands was guided by their attendance to the words and turns of phrase in the source material.

We also enjoyed a make-up tutorial and workshop by theatre artist Darian A. Leatherman, who taught students fundamentals of design, then helped them turn their own designs into realities.

Arora depicted Grendel as an emanation of the environment, with giant hands ready to scoop up thirty Geats.

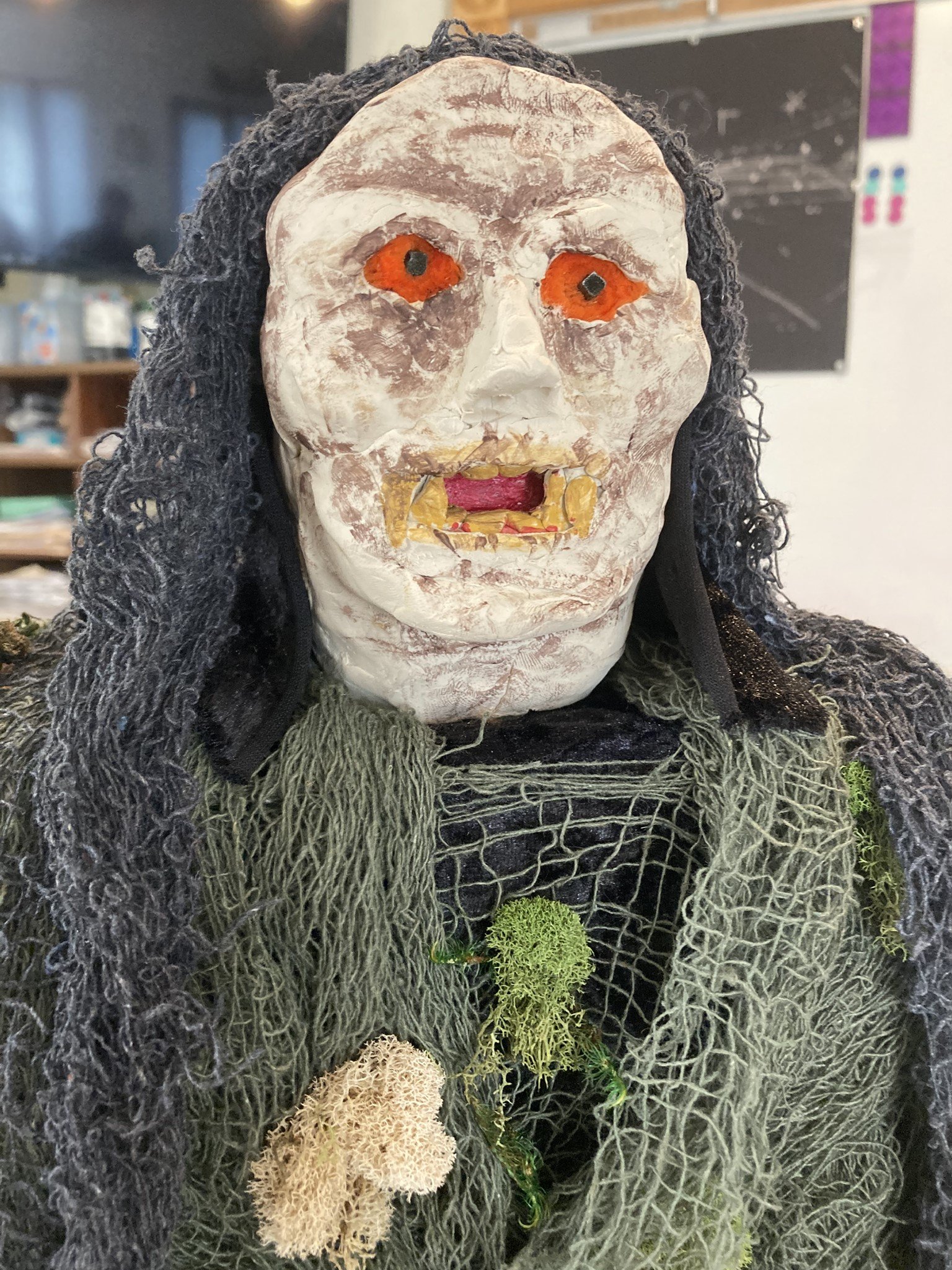

Finn's Grendel has the eyes of fire the Anglo-Saxon scop (poet) describes, mossy cloaks to connote his recent emergence from his swampland home, and a gaping maw. The cloaks' patterning evoke the chain mail worn by his adversaries, even as it evokes maritime netting.

Abby's Grendel blends the human with the avian, in particular the black vulture. In her presentation to the class on the explicit and implicit textual evidence that guided her drawing hand, Abby noted Grendel's human lineage and his bird-of-prey features, then mapped the black vulture's characteristics onto those the scop delineates. Abby's two images, one of the creature's head, and one that shows the hybrid skeletal structure of the monster, capture the unsettling contrasts at the heart of Grendel's terrifying nature.

Isabelle depicted Grendel returning, wounded, to his swampy lair, placing us, unnervingly, underwater.

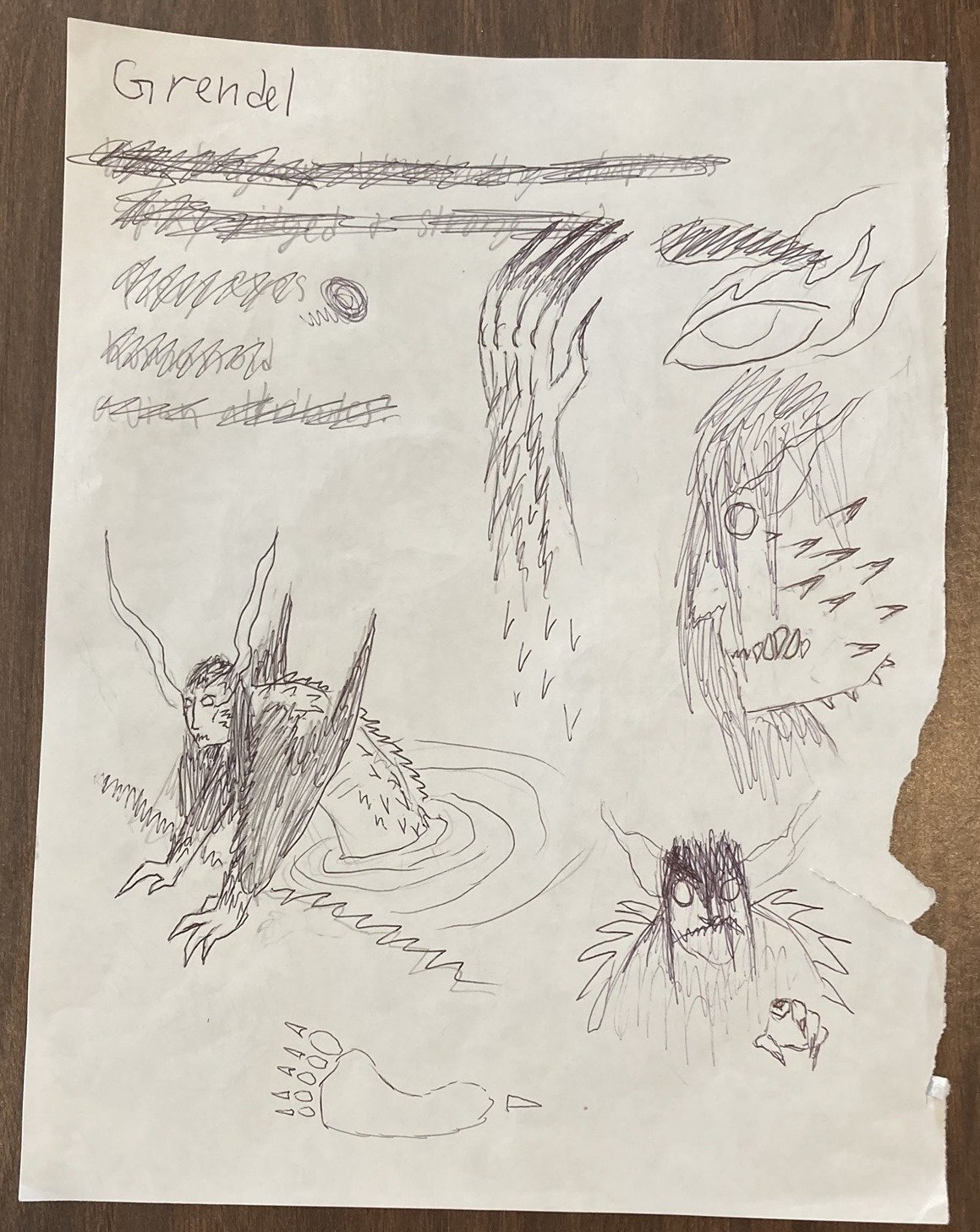

In Lydia's sketchbook, Grendel took on many forms--all unsettling, all a mirror of the unsettling fact that this monster's made of incongruous features and natures. "Every time I pictured him, he changed," Lydia told us in her presentation. The figures that emerged from her experimentation in imagining Grendel explore the source text's verbs ("It's mentioned twice that he 'swoops,' she noted, adding that that word's definition, when combined with the mention of "talons," compose a descending bird of prey), even as they dramatize the humanioid/avian mixture that strikes at the heart of the creature's fearsomeness. Along the way, she analyzed the text for subtle clues in imagery and turns of phrase that might suggest aspects of the creature's surface textures, and disposition. "Overall, the collage I did of him was fragmented," Lydia concluded. "I never drew all of him, for evidence about his appearance is antithetical and confusing. His actions speak louder than his descriptions."

Henry's Grendel took inspiration from some of the verbs the scop uses in the text (as rendered by Seamus Heaney in his translation). The creature's said to "lope" and to "swoop." The former's definition included a horse's gait, which informed the creature's legs, while the latter's definition, constellated with other mentions of Grendel's night-work, inspired the monster's night-filled wing-span, which, in the light, shows its feathers.