Bard College

Just before Thanksgiving break in 2020, we began our expedition into the works and days of Shakespeare (a course we called Bard College)

We began with a live performance (via Zoom) of an interlocking set of scenes, monologues, and sonnets by Shakespeare, selected and performed by Sanda Moore Coleman and Mr. Coleman.

We've explored the power of Shakespeare's language as experienced in a number of scenes and monologues, and then within the whole of Much Ado About Nothing (via a fantastic Globe Theatre Live performance from 2012, featuring Eve Best and Charles Edwards) and A Midsummer Night's Dream, a play that is a kind of synthesis of our three previous deep-dives (comedy, the moon, the law), for it is a comedy that is rooted in wonder which features characters who are moonstruck. It is a play that concerns the power of imagination and how that power can inform rationality. It is about the law, even as it is about love.

We also watched professional actors perform scenes and monologues in a workshop setting, via clips from Playing Shakespeare, a mid-1980s BBC series in which the director John Barton and a group of young actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company (including Judy Dench, Patrick Stewart, Ian McKellen, David Suchet, and Michael Pennington) workshop scenes and monologues in a directed but informal setting. They hold scripts in hand. They wear street clothes. There are few props. And yet each moment is full of life, fully formed, fully charged with meaning. (We recalled what Moliere once said: in theatre "all that's needed is a platform and a passion or two. The climax of this play [Our Town] needs only five square feet of boarding and the passion to know what life means to us.” This brought to mind what Woody Guthrie said about songwriting: "All you need is three chords and the truth.")

We watched different film versions of the same scenes (from Macbeth and from Much Ado) then compared and contrasted them as objectively as possible, using a form that invited observations about language, lighting, staging, costuming, etc.), so that our conclusions, our stated preferences, were based upon evidence.

We also discussed how historical forces are encoded in Shakespeare's works, such as how the climate of fear surrounding the Gunpowder Plot found expression in Macbeth, or how concerns about succession in Elizabethan England were explored in Julius Caesar. We discussed how it is that Shakespeare's works can remain so deeply relevant across time and space.

We studied tools of expression used by Shakespeare--antithesis, anaphora, allusion, imagery, alliteration, assonance, rhythm (including various metrical feet, forms of lines, and kinds of metrical substitutions)—, a study that helped us more fully inhabit and understand character, theme, and meaning within a wealth of monologues and scenes and within a play as a whole.

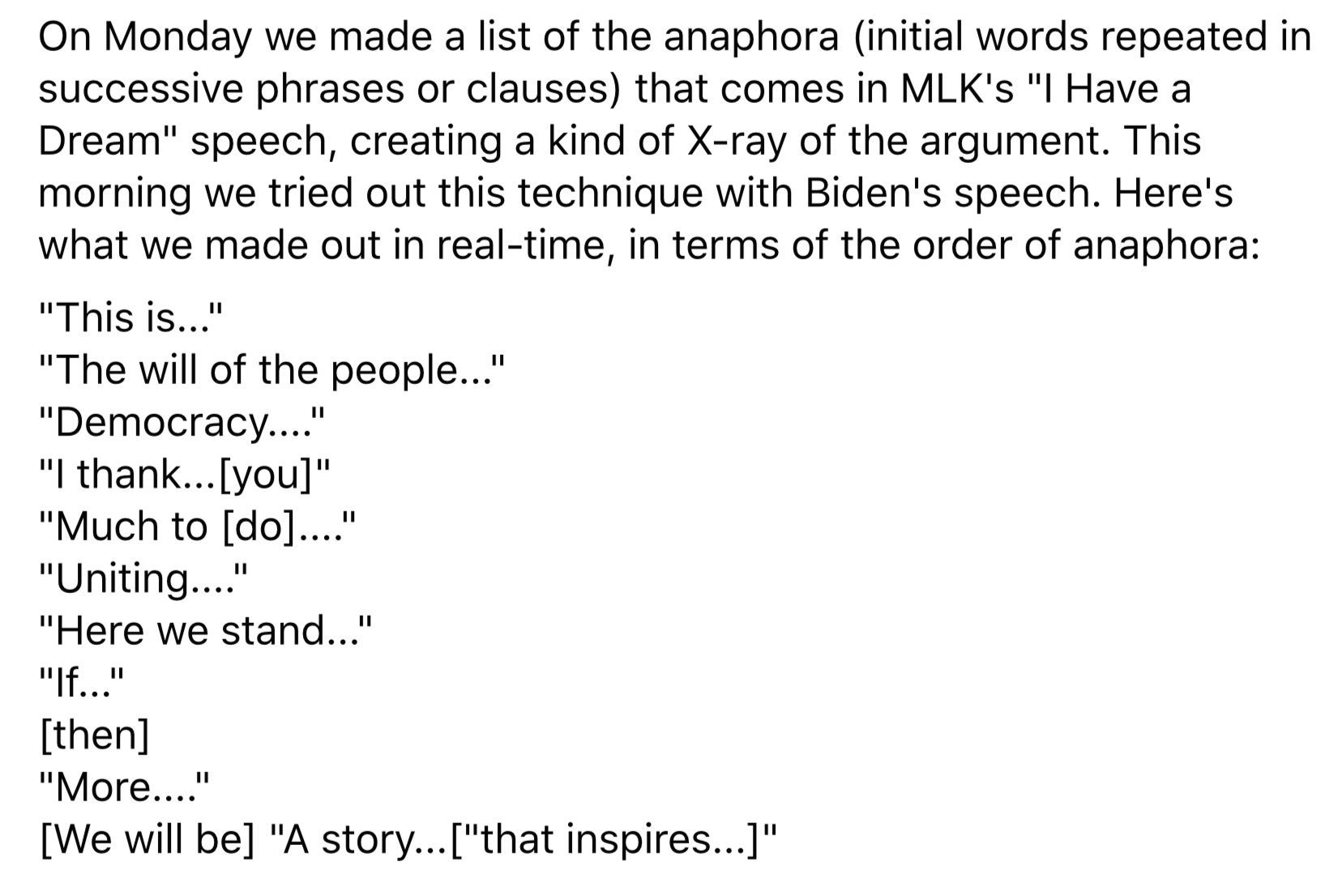

We used these same tools to help shed light upon the works of Martin Luther King, Jr. on MLK Day, when we watched and read and studied his "I Have A Dream" and "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speeches, as well as his sermon "The Drum-Major Instinct." We also read and saw Robert Kennedy's speech, which he delivered in the wake of MLK's assassination, and in which he quotes the Greek tragedian Sophocles in order to offer coordinates of compassion to his hearers.

Those same tools of expression allowed us to more fully inhabit the songs, speeches, and poems that composed the Inauguration, which we watched live on January 20, 2021. We analyzed certain works in real-time, and then made something of that inquiry: Ian, for instance, drew the roots of allusion embedded in Biden's speech, so that we could see the life of Lincoln and Winthrop and Isaiah and Langford Hughes that helped animate the meaning of the speech. We did the same kind of work with the Amanda Gorman's inaugural poem, "The Hill We Climb."

In analyzing the above works, we employed a tool of thinking, Part/Whole, in which we aimed to tether our analysis of a particular aspect of a piece (such as Gorman's near-exclusive use of first-person plural) to an observation about the meaning of the work as a whole (a theme of unity, for example).

Throughout the past weeks, we also continued our memory work and our creative writing, so that we could internalize these tools of expression. Students memorized and recited Mary Oliver's "White-Eyes" and wrote poems that enacted metrical forms.

(As we worked at understanding the tool of expression of assonance from the inside, we wound up inventing our own language, in which only the vowel sounds of words are spoken. Oliver dubbed the language Lag, since its sound is like that of someone cutting in and out on Zoom.)

Along the way, we've continued our practice of outlining (students outlined the tools of expression, then outlined the use of some of those tools within certain works) and continued our practice of analytical paragraphing (using the same form that we used in Comedy Class and Law School: Claim / Cite / Quote / Explain).

During project week, in addition to selecting, analyzing, and performing Shakespearean monologues, students were asked to make visible one or more tools of expression. The gallery below includes a sampling of what the students made of that inquiry, including a sculpture of Plato and Aristotle from Raphael's The School of Athens and a fashion show of metrical feet.

Students performed monologues from such Shakespeare plays as Much Ado About Nothing, A Midsummer Night's Dream, Hamlet, Julius Caesar, Henry V, Richard II, and Richard III.

Here's what Ian wrote about his work: This drawing is a representation of antithesis. There are several examples of such in this work. The two heads shown are blue and bluey-purple, to represent the contrast between the day and the night (this contrast is aided by the presence of a sun or a moon on each respective being’s forehead). On each face is also a mountain or a city skyline, to represent the natural world and the artificial world. The hair on each head is different, as well: the head of nature has hair of grass on the sides and hair of clouds on the top; the head of artificiality has hair made up of roads, with a strand on the side representing energy and the hair in the ponytail representing subways. However, since antithesis is the juxtaposition of contrasting words, images, or ideas in parallel structure, there are some similarities between the two heads as well. Both faces are made on a base of sky, both feature a major celestial body on their respective foreheads, and both feature tall formations on the nearest sides of their respective heads. There’s my presentation. I’m Ian Bench, and thank you for coming to my TED Talk.

West's painting, which he titled "Heavy Like a Balloon," exemplifies antithesis in a richly imaginative way. The class especially appreciated the way he rendered reflectivity on the surface of the balloon.

Lydia's expressive, thoughtful pair of paintings enacts antithesis in many ways. The left-side depicts "iamb," the metrical foot often associated with the heartbeat, and which, etymologically means "to step," (which she depicted with a relatively leisurely heart rate). By contrast, the trochee is an inversion of the iamb (the heart is inverted, and defined by negative space surrounded by dappled green, red's opposite on the color wheel). Etymologically, "trochee" means "to run," thus elevating the pulse.

Arora chose to make clay models of Plato and Aristotle, from Raphael's The School of Athens, in order to depict antithesis and allusion. Arora placed the figures in a natural setting, one that retained the visually-echoing archways of the original Raphael work. As she explained in her oral presentation of her work, the figures of Plato and Aristotle represent differing views, ones that contrast in their ultimate focus: an ideal world of forms as opposed to the sensory world of Earth. She then added that, since Raphael himself was using these figures' gestures to allude to those contrasting philosophies, and since she (Arora) was alluding to Raphael's work by sculpting only those two figures (out of dozens in the original), her work was, essentially, "an allusion of an allusion."

Gideon depicted the clarifying effect of anaphora on the reading of texts. As he explained, his ADHD can cause him difficulties in readily making sense of a text; the words can seem disorganized (illustrated by the main portion of the painting, in which black marks leave random tracings and loopings). However, when a figure of speech such as anaphora is used by the author and then detected by Gideon, that figure has the effect of bringing that disorder into order (depicted by the band of crimson that contains shades of the inky text). He then added that the proportions of the composition (the crimson band composing a small fraction of the overall compositional space) reflect the reality that such clarifying figures of speech are, in themselves, as fraction of the overall amount of words in a text, while their effect is profound (symbolized by the bold color red)

Finn depicted metrical feet through the medium of clothing. His choices were thoughtful: his "iamb" (on the right in this photo) was depicted with casual, everyday wear, in keeping with the fact that, as he said, "it is the most common foot." Dactlyl--a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables--is depicted at left in the photo, with the red had marking the punctuated first syllable.

To illustrate iamb's opposite, the trochee (at right in the photo), Finn fittingly used formal wear, even using a tie as a kind of exclamation point that demonstrated the initial stressed syllable. The anapest is rendered as regal attire, for the foot sounds to Finn like the trumpet fanfare for a monarch.

The spondee, fittingly, is depicted by two bold, clashing, yet structurally similar, articles of clothing

Tori's artwork, depicting antithesis, illustrated the meaning of a line from Amanda Gorman's Inaugural poem, "The Hill We Climb": "We lay down our arms so we can reach out our arms to one another." Tori's art explores the different meanings of "arms," and the different ways "arms" may be used.

Some of the antitheses and allusions we discerned in MLK's "I Have a Dream" speech.

We outlined the allusions we found in Biden's inaugural speech.

Ian then drew the roots of allusion that gave rise to the speech.

A compilation of four student responses to question #16 on our test on Shakespeare, rhythm, and invention!

We also watched professional actors perform scenes and monologues in a workshop setting, via clips from Playing Shakespeare, a mid-1980s BBC series in which the director John Barton and a group of young actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company (including Judy Dench, Patrick Stewart, Ian McKellen, David Suchet, and Michael Pennington) workshop scenes and monologues in a directed but informal setting.

Here is a young Ian McKellen and a young David Suchet!

We also watched this fantastic production of Much Ado, filmed live at the Globe Theatre in London, in 2012.

“All Is Mended,”

an interlocking set of scenes, monologues, and sonnets by Shakespeare, selected and performed by Sanda Moore Coleman and Mr. Coleman.