The Design Principles of Poetry

In April 2022, we took a dive that led us to a deeper understanding of poetic form, including the shapes of villanelles, acrostics, ballads, haiku, limericks, Bantu call-and-response poems, and others. At the same time, we studied design elements common to many forms of poetry: diction, syntax, ambiguity, metaphor, simile, imagery, metrical feet, enjambment, etc.

We engaged in close readings of exemplars of each form, looked at historical and cultural associations associated with the forms, and then tried our own hands at each one to exercise our understanding and imaginations.

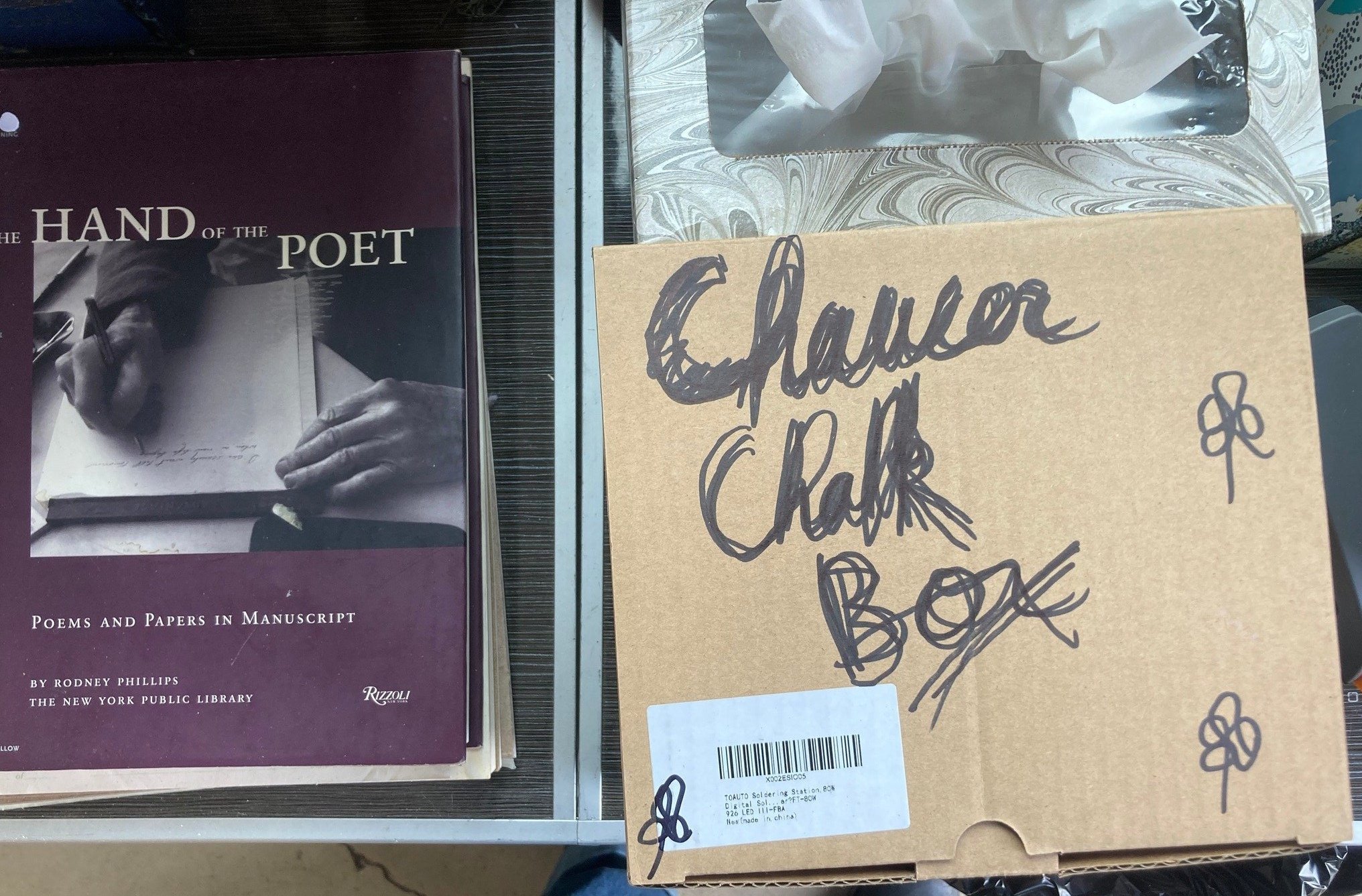

And, as we do each April, we memorized the opening lines to Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, and recited them beneath The Star-Splitter sycamore tree on the campus of Friends University.

We also engaged in in-class discussions and in-class analytical writing that exercised our understanding of how the design principles help to create meaning within given works (i.e., how does Chaucer’s use of antithesis tether to a larger thematic concern in Prologue to The Canterbury Tales; why is Howard Nemerov’s use of polysemy apt in “Because You Asked About the Line Between Prose and Poetry”?).

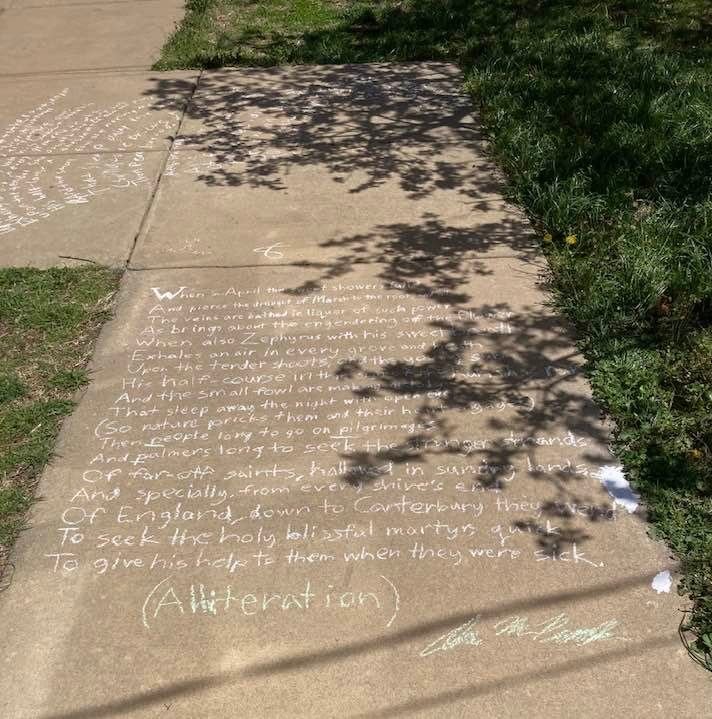

Also, as you’ll see in the gallery below, one morning, when the Internet was down and the copy machine was down, we grabbed our sidewalk chalk, which is always at the ready. First, each of us wrote out Chaucer’s opening lines from The Canterbury Tales; each Star-Splitter then identified and highlighted a figure of speech or other design element within the text. Then we invented a walking renga, with each Star-Splitter creating a three-line haiku or a two-line waki in their respective sidewalk squares.

First, each of us wrote out Chaucer’s opening lines from The Canterbury Tales; each Star-Splitter then identified and highlighted a figure of speech or other design element within the text. Then we invented a walking renga, with each Star-Splitter creating a three-line haiku or a two-line waki in their respective sidewalk squares.

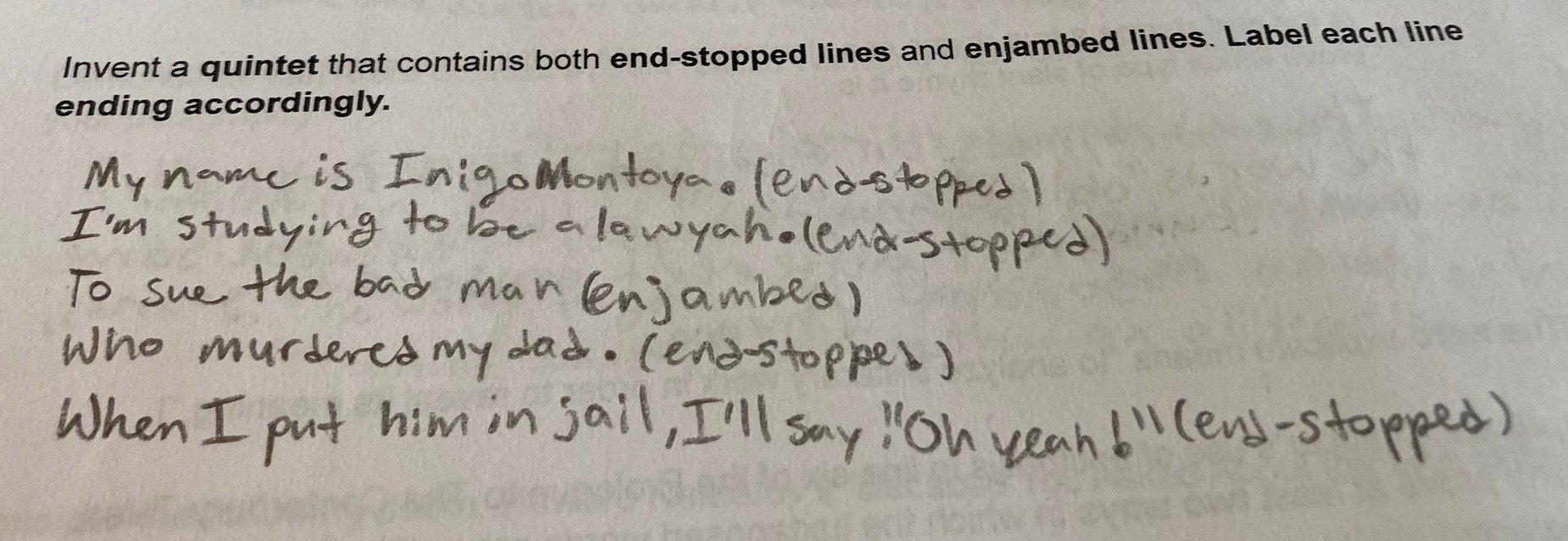

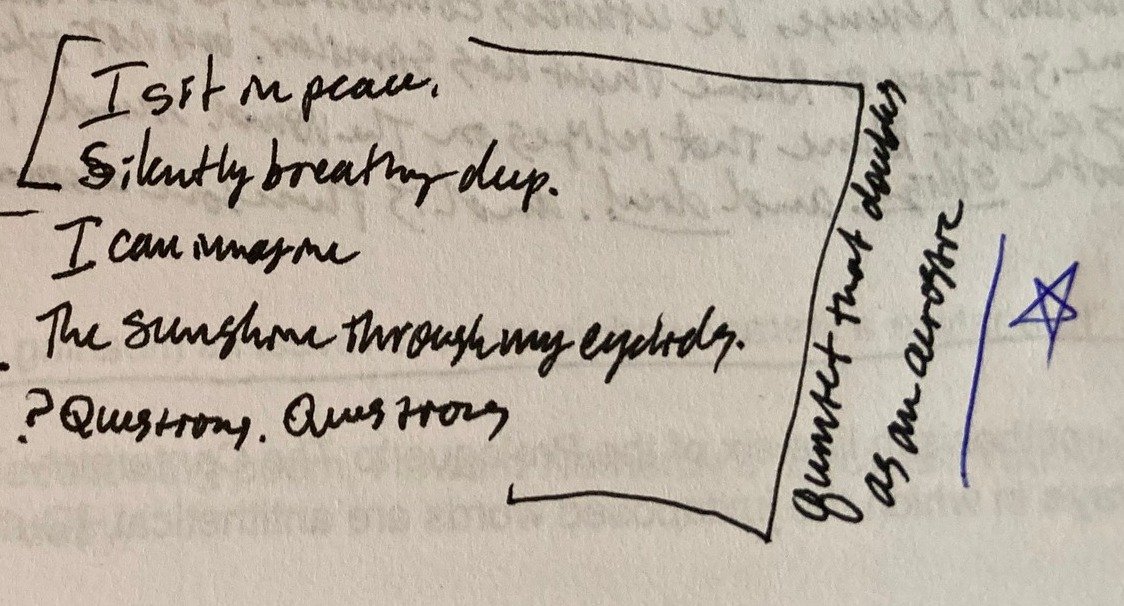

It's fun to grade papers when you have great students. Here are some answers to a question from our Design Principles of Poetry deep-dive, which asked students to create a poem using both enjambed and end-stopped lines.

"Quintet that doubles as an acrostic"

After writing some lines of poetry that demonstrated their understanding of metrical feet, including the establishment of a prevailing foot and the use of substitutions, Oliver decided to add a pie graph of their choices!