If the Shoe Fits: A World History of Cinderella

In January-February 2022, the Star-Splitters took a deep-dive into world history, literature, and sociology, "If The Shoe Fits: A World History of Cinderella," in which students read a wealth of Cinderella stories spanning millennia and miles.

Such close readings included accounts of an ancient Egyptian proto-Cinderella tale recorded by Greek historians Herodotus and Strabo, as well as the Cinderella story told in T'ang Dynasty-era China, the one Charles Perrault wrote to suit Louis XIV's court in France, and the one The Grimm Brothers composed in the nineteenth century to unify a disparate people within a single national identity.

We surveyed the many interpretive lenses used to see fairy tales, from psychology to sociology, linguistics to political science.

And we delighted in the space that fairy tales allow us to inhabit in our imaginations.

What threads the many versions of this tale together; what's revealed by the differences? Why do we tell stories? Why do we listen to them?

The class was led by Sanda Moore Coleman, former Harvard teaching fellow and winner of the Poets and Writers Maureen Egen Award for fiction.

Sanda shared her formative experiences as a reader of fairy tales, shared Lisel Mueller's "Why We Tell Stories," and then led the students into the creation of their own tales: What's in your bindle? she asked, as she showed the image of Jack seeking his fortune in an old volume of English fairly tales.

The students chose three objects that would help them, respectively, in their meeting with a mentor, their navigation of dangerous territory, and their encounter with the "wolf." They were free to define those terms however they liked. The stories that emerged in the hours we were together were wonderful and often profound and inspired our graduation ceremony.

We then turned toward the history of Cinderella. In reading each story, we were alert to the ways in which the texts reveal values and culture, the ways in which historical moments found their ways into the writing, why the story spoke to the times and cultures in question. The students identified a range of meaningful differences among the stories, each of which was revelatory of the unique time and place in which the story arose.

At the same time, we looked at the many ways in which the various versions chimed. We kept track of common elements and themes; we explored Joseph Campbell's monomyth. We stood in wonder at how the story appears in different forms around the world.

To help gain purchase on those revelatory differences and commonalities, students learned how to craft comparison/contrast essays, starting with data-collection from the primary texts, moving to the arrangement of that material using graphic organizers such as Venn diagrams or outlines, and then concluding with the presentation of findings, via the writing of clearly structured, well supported paragraphs and essays that demonstrate understanding of vital points of intersection and divergence.

For Maker Week, students demonstrated their understanding of all we've learned in ways that, as always, united creativity and analysis.

Students made their own Cinderella stories, engaging with or breaking from the tradition in terms of six elements that we found common to many of the existing tales—and thus making the story new for their time.

The stories were accompanied by analytical comparison/contrast papers that interpreted their interactions with the tradition.

Students then celebrated and anlayzed one another’s stories. As Abby noted one day when we were comparing and contrasting students' original Cinderella stories with versions from China, Greece, France, Scotland, and Germany--a process that saw students energetically flipping through their binders so that they could support their analytical claims with specific evidence drawn from the primary source material--, "We're like literary lawyers!"

Finally, students created illustrations for one another's Cinderella stories. This assignment was designed to be an extension of our work in learning how to create a trusting, joyful, and generative community, how to have constructive conversations, even across differences--all of which begins by seeing and hearing another's position clearly and generously.

We develop these same skills when we play improv games that cultivate active listening and the joyful seeking of areas of agreement. We also practice these skills when engaging in conversations that follow Rappoport's Rules, the first of which is to say back to someone their own argument or statement in such a way that that person recognizes it as a fair and even winsome depiction of their own position, undistorted.

In these ways, the act of faithfully seeing another person's story, evidenced by an illustration that does it justice, is an expression of Star-Splitter-style community-building.

Finn drew the Fairy Godmother's hat and wand on the board so that everyone could take a turn becoming the mentor!

Jiggety-Jolt! Jack and his bindle and his cohorts, seeking their fortune!

This is an image Sanda saw when she was a little girl: The Three Little Pigs, with bindles-- and a backpack!

The first page of Arora's bindle story, which won an award at the 2022 Kansas Voices Writing Contest

The first page of Lydia's Cinderella story, which won first place at the 2022 Kansas Voices Writing Contest.

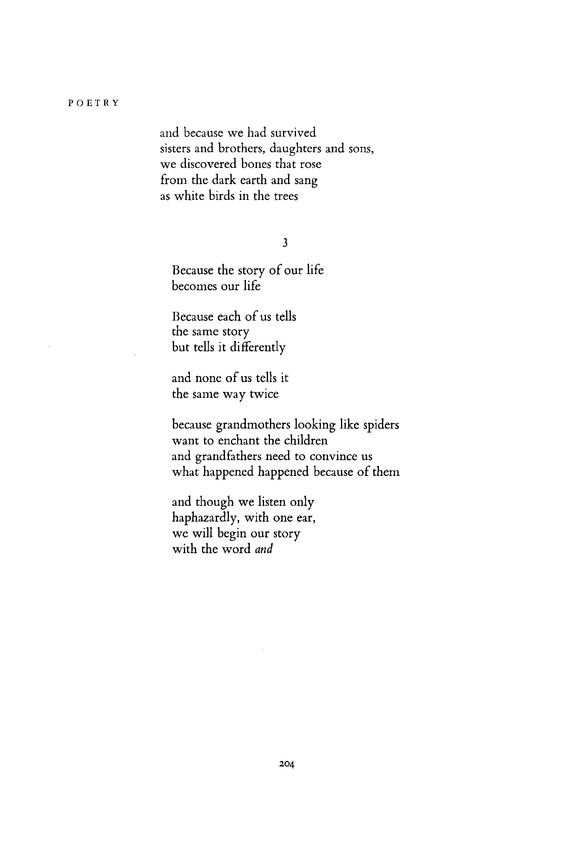

"Why We Tell Stories," as it first published in Poetry Magazine in July 1978. We read this work each morning during our deep-dive into Cinderella stories. The poem reminds us that the story of our life becomes our life, and that our stories are rooted in the idea of “yes and.”

"Why We Tell Stories," as it first published in Poetry Magazine in July 1978. We read this work each morning during our deep-dive into Cinderella stories. The poem reminds us that the story of our life becomes our life, and that our stories are rooted in the idea of “yes and.”

A well deserved standing ovation for Sanda Moore Coleman on the last day of the deep-dive.

The Star-Splitters celebrated the snow in February by creating snow-allusions to things we've studied. Henry's snowllusion was to Cinderella. This snow slipper was left behind...

...by...

...a GIANT!

The Star-Splitters celebrated the snow in February by creating snow-allusions to things we've studied. Oliver's snowllusion was to "Little One-Eye, Little Two-Eyes, and Little Three-Eyes," a variation on the Cinderella story. Here is Little One-Eye.

Little Two-Eye...

And Little Three-Eye.

During the time of our deep-dive, Isabelle made a Star-Splitter logo in her stained-glass making class. Here it is casting its colorful shadow on the blinds of a window in our classroom!